2022 Blogs

Want Equal Pay? Get a Union.

By: Wendy Chun-Hoon, Liz Shuler | February 15, 2022

Leslie Cotton, a union plumber from Oregon

Aurora Bihler waited tables for years. Despite being more experienced than her male co-worker, she later learned that he was paid more doing the same job. That all changed when she joined Ironworkers Local 396 in St. Louis eight years ago. Not only was this a higher paying job, but she also worked alongside her male counterparts as an equal, and was able to buy a car and her own home. She credits being in a union for helping her achieve what is out of reach for too many working women – financial independence. To pay it forward, she is now focused on helping women and diverse candidates enter the union building trades so they can have the same opportunities through a program called the Missouri Works Initiative. Her Valentine’s Day wish is for more women to experience the transformative difference a union can make in their own lives.

Aurora’s story is not unique. The Bureau of Labor Statistics findings are clear. Unionized women make on average 23% more than women without a union. They are also far more likely to have paid leave and stronger protections against discrimination and sexual harassment in the workplace. So yesterday we not only observed Valentine’s Day, but also Union Women Equal Pay Day – when union women reach what men earned in 2021 – ahead of when non-union women catch up.

Union Women Equal Pay Day comes a full month earlier than Equal Pay Day for all women because of the significantly smaller pay gap between unionized women and men. Being represented by a union reduces women’s wage gap by nearly 40 percent compared to the pay gap experienced by non-union women. For Black and Latina women, the union advantage is even greater. This translates into hundreds of thousands of additional dollars in union women’s pockets over the course of their careers.

Greater pay equity exists for union workers because of the transparency and equality provided by a union contract. Collective bargaining agreements apply to all workers at a job, regardless of their race or gender. Importantly, workers with unions feel more secure speaking out about pay and other workplace issues, because they know they have the power of a union.

Some may wonder why Union Women Equal Pay Day isn’t Jan. 1? Why is there a pay gap at all?

The answer lies in the jobs women do – men still hold the highest-paying jobs in our economy in construction and manufacturing, so women’s pay, mostly in service occupations and industries, on average, is lower. This is a persistent problem that suppresses the wages of women and workers of color – and even more so for workers without the benefit of a union. Creating opportunities for women like Aurora in these higher-paying jobs is a top priority for both the Biden-Harris administration and the AFL-CIO.

In order to ensure equal pay across the board, the Biden-Harris administration established the White House Task Force on Worker Organizing and Empowerment to find ways that federal government agencies can use their authority to support the formation of unions. The task force just released its first report, containing nearly 70 recommendations. At the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau, we are finding ways to get information about organizing and bargaining rights into the hands of more workers, so more working women will know about opportunities they have to form a union. And we are going to work with other agencies on a Unions and Collective Bargaining Resource Center, so more workers will have information about the many ways having a union can improve their lives.

Union approval is the highest it has been in nearly 50 years, with 60 million non-union workers saying they would vote for a union if they could. Now is the time to act. Encourage the women in your lives to get union cards.

Wendy Chun-Hoon is the director of the Women’s Bureau at the U.S. Department of Labor. Liz Shuler is the president of the AFL-CIO, a federation of 57 national and international unions representing 12.5 million workers.

Building Back Better: Centering Equity and Inclusion in Job Creation and Economic Development

By: Elyse Shaw | February 14, 2022

This is a pivotal moment for the U.S. economy. After record job losses due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy is slowly recovering: Employment continues to grow and unemployment rates are falling, although these improvements still lag behind for women, especially Black women. Unprecedented levels of public investment from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will help this upward trend continue by creating good middle-class jobs that many workers urgently need. However, most of these IIJA-funded job increases will be in the construction trades, where women and people of color are vastly underrepresented. At this pivotal time in our history – with the largest ever investment in public infrastructure – we must ensure that women and communities of color are included in these economic opportunities.

On Feb. 24, 2022, the Women’s Bureau and The Worker Institute at Cornell ILR will launch a webinar series, “Equity in Focus: Job Creation for a Just Society.” We will cover current research and programs that address the need for an equitable economic recovery. The first webinar will explore how equity in job creation is defined, with a focus on the current expansion of infrastructure investment.

According to Andrea Flynn, senior director at Insight Center and one of the webinar panelists, equity is eliminating barriers to accessing opportunities. When it comes to employment, equity means equal access to educational and career advancement, and to jobs that provide people with the income needed to take care of their families and improve their economic well-being. Yet, women and people of color are often overrepresented in low-wage, unstable jobs that lack essential benefits. This occupational segregation is one of the biggest barriers to economic equity for women and people of color. Equity will only be achieved with intentional interventions that acknowledge the longstanding marginalization of women and people of color within the labor market. Additionally, interventions need to center worker voices, focusing on those who are the most disadvantaged.

There are already real-world examples of successful policies that intentionally address gender and racial disparities within the construction trades, including the Construction Career Pathways policy framework, which will be highlighted in the webinar. This framework is a set of strategies that centers racial and gender equity in job creation. It was developed by 16 public agencies, with significant input from industry and community stakeholders. Raahi Reddy, director of Metro Regional Government’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion program, led the initiative to develop the Career Pathways framework and works closely with various partners, such as Oregon Tradeswomen. The framework boils down to four key strategies:

- Setting concrete goals to increasing demand for a diverse workforce on publicly funded construction projects.

- Investing in the recruitment and retention of women and people of color within the construction trades, including anti-harassment and respectful workplaces training.

- Establishing clear expectations for building trades partners through workforce agreements.

- Building intentional partnerships through continued collaboration, which includes meeting regularly to evaluate how the work is progressing.

Before the Career Pathways initiative, Oregon Tradeswomen and others had been working on increasing diversity in the construction trades for years, but significant and widespread scaled progress was still far off. Kelly Kupcak, executive director of Oregon Tradeswomen, shared that “the Construction Career Pathways project is unique in that it shifts the way we do this work to shared prosperity model while also taping into the collective expertise and experience from organizations doing the work on the ground.”

Using examples such as the framework in Portland, now is the time to design and implement policies and programs that will dismantle structural barriers and achieve equity and inclusion in economic development through high-quality jobs access for women and people of color across the United States. The IIJA provides the nation a unique opportunity to do exactly that – to build our labor force back better, benefiting not only the individual workers, but our economy and the nation.

To learn more, join us for the first webinar of our equity in employment series on Thursday, Feb. 24 at 12:30 pm. Register here.

Elyse Shaw is a policy analyst in the Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

Black Women’s Economic Recovery Continues to Lag

By Sarah Jane Glynn, Mark DeWolf | February 9, 2022

The jobs data for January 2022 far exceeded expectations in job creation in the midst of the ongoing Omicron variant wave. The private sector added 444,000 jobs, driven by growth in leisure and hospitality, professional and business services, retail trade, and transportation and warehousing. The overall unemployment rate remained little changed at 4.0%, and accounting for upward revisions of prior months’ data, President Biden’s first year in office ended with a total of 6.6 million jobs gained.

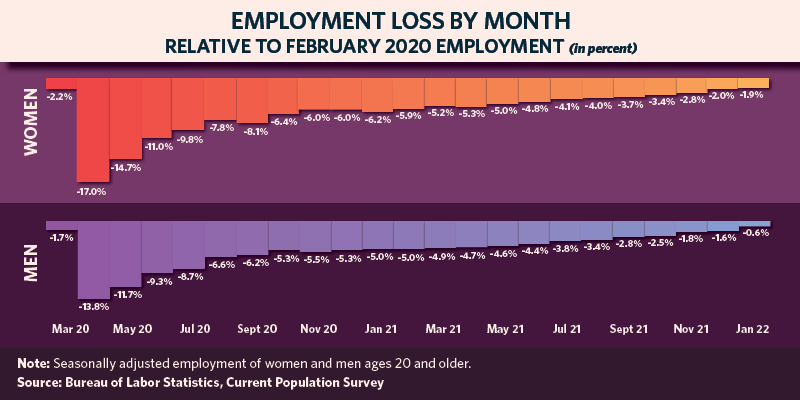

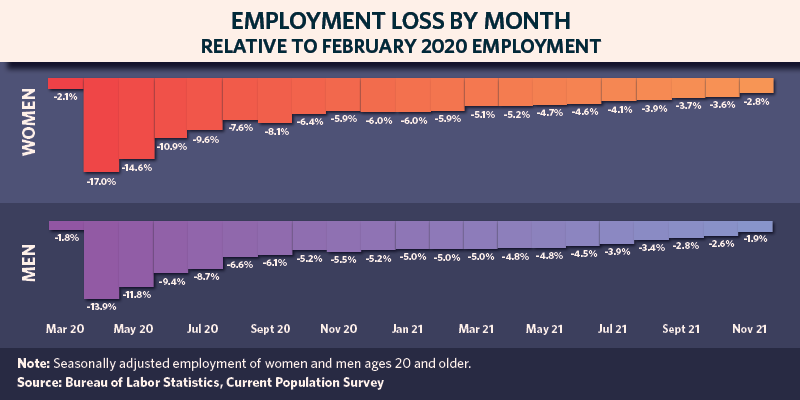

However, most of the job gains have gone to men, with women only gaining 40.3% of jobs in January and 40.1% of total new jobs over the last three months. Women workers are still down 1.8 million jobs relative to February 2020, while men are down 1.1 million jobs. And there are still 1.4 million (1.9%) fewer employed adult women than pre-pandemic, compared to 500,000 (0.6%) adult men.

(The difference between the number of jobs and employed women is influenced by the fact that women are more likely than men to hold more than one job.)

Caption: Click to see the source data for women’s employment. Click to see the source data for men’s employment.

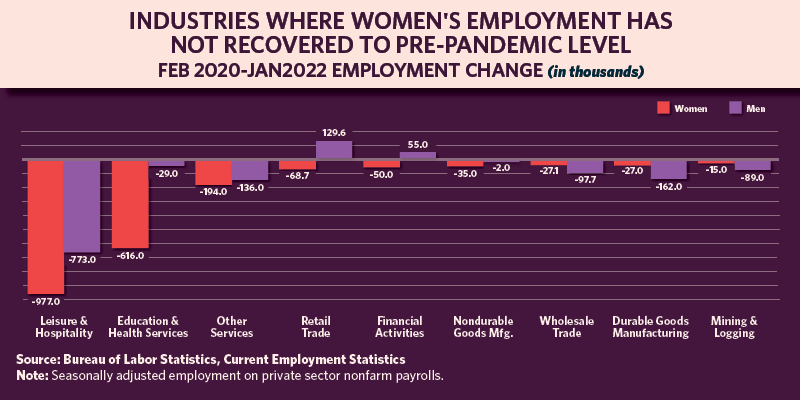

These gendered differences are largely driven by occupational segregation with women more likely to work in the sectors of the economy that lost the most jobs. There have been recent gains in sectors that were disproportionately impacted by shutdowns and decreased demand like leisure and hospitality and the retail trade. But these gains have not been enough to overcome the devastating job losses – most of them incurred by women – in 2020. As of January 2022, women workers are still missing over 616,000 education and health services jobs and over 977,000 leisure and hospitality jobs relative to when the pandemic began.

Caption: Scroll down for links to the source data.

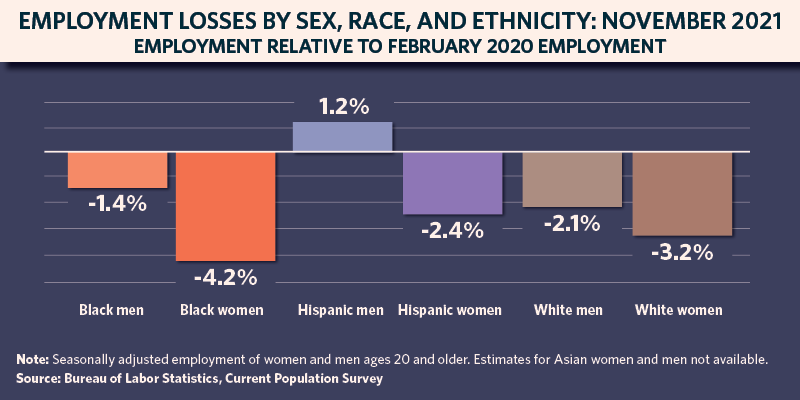

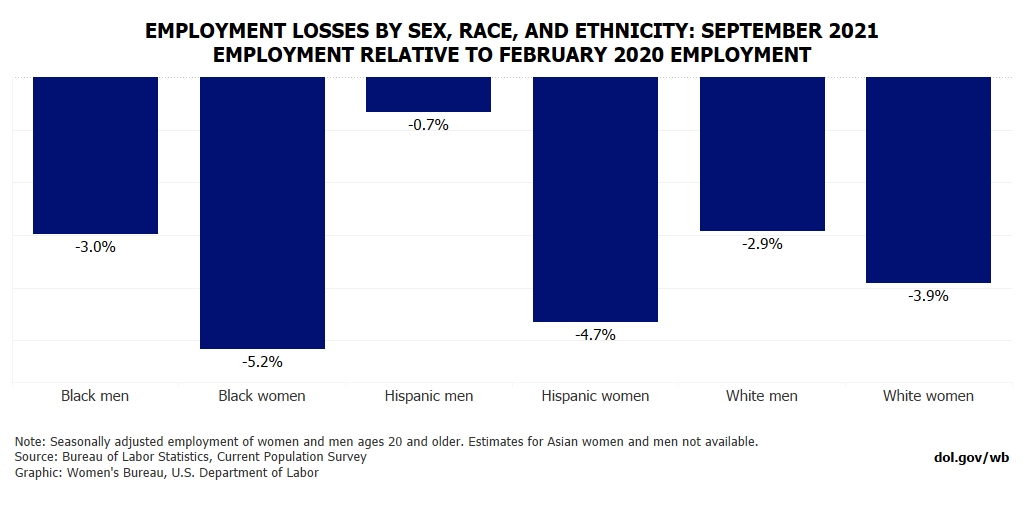

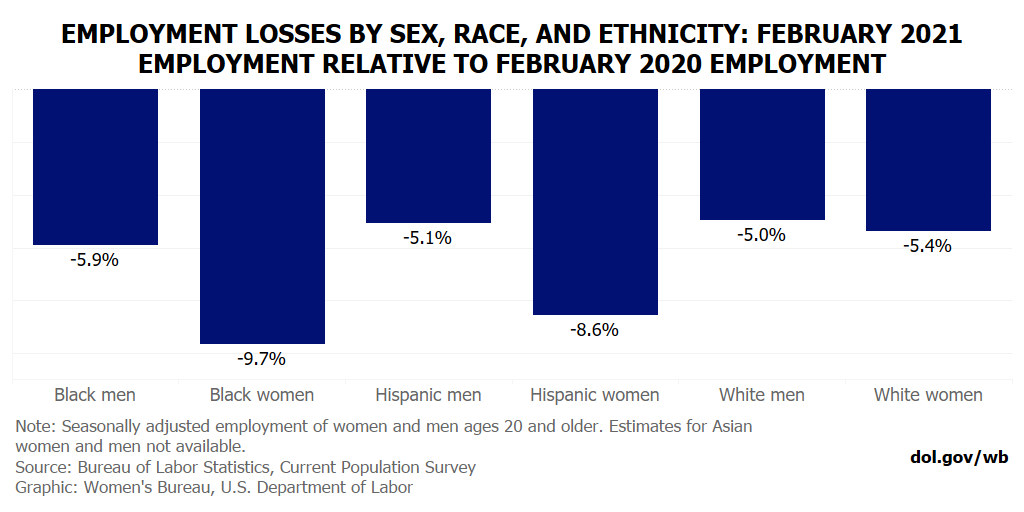

But these topline statistics on employment outcomes for women and men mask significant differences by race and ethnicity. Black and Hispanic adult women experienced the steepest job losses during the pandemic, but their recoveries have diverged recently. Since November, Hispanic adult women’s employment gains are outpacing those of adult Black and white women. Adult Black women’s unemployment rate is 1.8 times their white counterparts, is the highest among women and men by race and ethnicity (5.8%), and is still a full percentage point above its pre-pandemic level. Black women’s employment has recovered the least among major race and ethnicity groups, with 2.6% fewer adult Black women employed in January 2022 than February 2020.

Caption: Scroll down for links to the source data.

The different experiences of Black women in the pandemic and the recovery are caused by multiple overlapping factors:

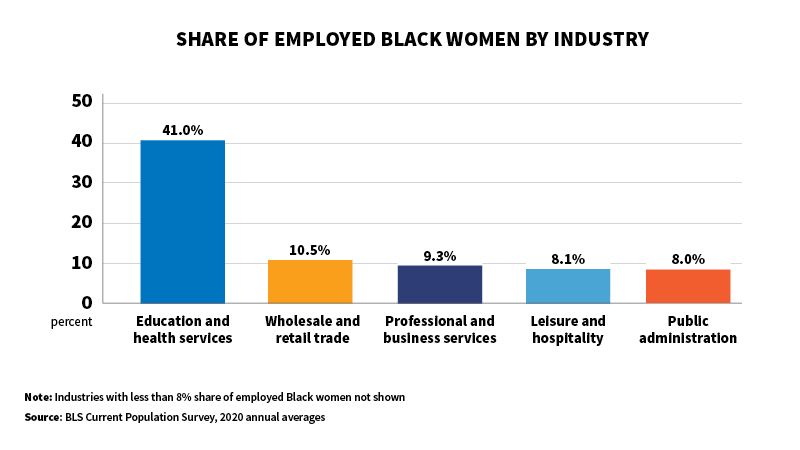

- First, before the pandemic Black women were disproportionately likely to be employed in some of the hardest hit sectors. For example, in 2019, Black women made up only 6.6% of all employees in non-agricultural industries but were 11.6% of all employees in education and health services.

- Data from prior recessions shows that when there are economic shocks, Black and Hispanic workers are more vulnerable to losing their jobs and recovery takes longer for Black and Hispanic women. While Black women were slightly more than 1 in 10 workers in the education and health services industry in 2019, when comparing annual data from 2019 to 2021 they represent roughly 1 in 6 (17.4%) jobs lost.

- Black women also are overrepresented in the care economy, and the ongoing crisis in this sector continues to have a disproportionate impact on Black women.

The intersection of racism and sexism means that Black women are experiencing a different, and more difficult, recovery not just because of the types of jobs they are likely to hold, but also because they are treated differently within those jobs. One way to help dismantle the barriers facing Black women is to ensure that all new jobs embed equity into hiring and promotion practices. Through our Good Jobs Initiative, we’re improving job quality and creating access to good jobs that are free from discrimination and harassment. Find information about the Good Jobs Initiative here.

Sarah Jane Glynn is a senior advisor and Mark DeWolf is a senior economist in the Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

Source data:

Click to see source data for Black men’s employment.

Click to see source data for Black women’s employment.

Click to see source data for Hispanic men’s employment.

Click to see source data for Hispanic women’s employment.

Click to see source data for white men’s employment.

Click to see source data for white women’s employment.

Click to see source data for Leisure and hospitality employment.

Click to see source data for Leisure and hospitality women employees.

Click to see source data for Education and health services employment.

Click to see source data for Education and health services women employees.

Click to see source data for Other services employment.

Click to see source data for Other services women employees.

Click to see source data for Retail trade employment.

Click to see source data for Retail trade women employees.

Click to see source data for Financial activities employment.

Click to see source data for Financial activities women employees.

Click to see source data for Nondurable goods manufacturing employment.

Click to see source data for Nondurable goods manufacturing women employees.

Click to see source data for Wholesale trade employment.

Click to see source data for Wholesale trade women employees.

Click to see source data for Durable goods manufacturing employment.

Click to see source data for Durable goods manufacturing women employees.

Click to see source data for Mining and logging employment.

Click to see source data for mining and logging women employees.

For Black Women, Implicit Racial Bias in Medicine May Have Far-Reaching Effects

By Joan Harrigan-Farrelly | February 7, 2022

This past December, Vice President Kamala Harris launched the first Maternal Health Day of Action and announced a White House call to action to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity rates in the United States. Vice President Harris described it as a crisis for Black mothers and stressed the urgency of “pursuing systemic policies that provide comprehensive, holistic maternal health care … free from bias and discrimination.”

Indeed, the U.S. has among the highest maternal mortality rates in the developed world, and much of these deaths – 60%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – are preventable. And even within this context, the likelihood of dying from a pregnancy-related cause is 2.5 times higher for a Black woman in this country than for a white woman. In 2019, the maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black women was 44.0 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared with 17.9 deaths among white women.

Why are Black maternal deaths occurring at such alarmingly high rates? One factor is implicit bias within the health system and among some health practitioners. From lack of access to quality care facilities to subpar treatment at the hands of providers, the legacy of racism in America continues to negatively affect Black health outcomes.

In a recent study, the National Institutes of Health found that healthcare providers were less likely to identify pain in the facial expressions of Black faces than on the countenances of non-Black ones. Because they couldn’t see it, they were less likely to believe a Black patient was experiencing severe discomfort or acute pain. This research is echoed in the voices of many Black mothers who recounted stories of being devalued and disrespected by medical providers during pregnancy and childbirth.

Sadly, despite these increasingly common narratives about maternal deaths, the U.S. health care system has been slow to recognize the role of implicit bias and systemic racism in poor health outcomes for Black women, and especially the role it plays in their higher rates of maternal death. It’s telling that this past December, an illustration of a Black baby in utero developed by a Nigerian medical student went viral because of the novelty of the image, with many respondents noting the rarity of darker skin tones in medical illustrations. Representation matters, and the absence of it, in textbooks and elsewhere, has disparate, and sometimes disastrous, consequences.

Medical and academic institutions are examining ways to tackle this crisis. Florida Atlantic University’s Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine has revised its curriculum to incorporate training on the impact of implicit bias in medicine: “Medical students start learning about racism in health care during their first year, and as they go, they also learn how to communicate with patients from various cultures and backgrounds.” At the state level, Michigan and California have made implicit bias training a requirement for healthcare provider licensure. The National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health has developed an action plan to assess their current policies and practices and determine the gaps that exist and the steps they can take to combat bias and discrimination in patient care.

Beyond the obvious impact on their physical, mental and emotional health, Black women may also face the devastating effect of these experiences on their financial well-being. The pregnancy complications resulting from racially motivated differences in treatment protocols may lengthen a woman’s recovery time, which translates into extended, likely unpaid, leave from work. For those without the employment flexibility to return to their jobs after a prolonged absence, adverse health outcomes may lead to indefinite departures from the workforce.

Unfortunately, Black women face a unique double-bind of racialized medical mistreatment and the lack of paid leave that would allow them to recover physically from a medical ordeal without enduring long-term financial repercussions. In fact, Black women are statistically among the most likely to need leave but not take it, even when their own health is at stake. Implicit bias and the lack of a national paid leave program, including parental leave, is a real hardship for many and an obstacle to employment and economic security. For the countless women with told and untold stories of trauma, it is imperative that we both acknowledge and amplify Black women’s voices in advocating for their health, and in doing so, rewrite the narratives around Black maternal health.

Learn more about the work of the Women’s Bureau, including employment protections for workers who are pregnant or nursing.

Joan Harrigan-Farrelly is the deputy director of the Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

The Kids (and the Adults) Aren’t All Right: Job Losses in the Care Sector Extend Beyond Child Care

By: Janelle Jones, Sarah Jane Glynn | January 11, 2022

The employment landscape looks much better for workers now than it did a year ago, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics' December jobs report shows. Although the December data predates most Omicron impacts on the labor market, it is encouraging to see that employment continues to increase and the overall unemployment rate has continued to tick down. In December the unemployment rates declined for adult men and adult women (both at 3.6%) – but this was largely driven by changes among white workers as the rates for Black, Asian and Hispanic workers showed little to no change. Things are moving in the right direction, but there is still more to be done to ensure that workers of color – who are often concentrated in low-wage work and are some of the most vulnerable workers – have access to quality jobs and pathways to success.

In addition to masking the differences by race and ethnicity, an overemphasis on topline unemployment figures does little to highlight the challenges facing particular occupations and industries. Adult women’s labor force participation increased slightly in December to 57.8% (+0.3%) and remains at pre-pandemic lows not experienced in more than three decades. Women workers are still down 2.1 million jobs, and women’s employment is fully recovered in only four industries: utilities, professional and business services, construction, and transportation and warehousing. And it is worth noting that three of these four industries employed relatively few women before the pandemic – utilities (19.9% of employed workers were women in 2019), construction (10.3%), and transportation and warehousing (24.8%) – making the recovery back to the baseline even less meaningful in relation to women’s overall employment.

While women have made gains in non-traditional industries (defined as those with less than 25% women), many traditionally feminized sectors continue to have significantly fewer workers compared to pre-pandemic numbers. Some of this, such as the decline in jobs in the leisure and hospitality sector, may be due to decreased demand and closed businesses. However, other traditionally women-dominated industries are primarily composed of essential jobs performing labor that provide a foundation necessary for the economy to function. The care sector is a prime example of this phenomenon. As we have seen throughout the pandemic, when care infrastructure – whether for children, people with disabilities or older adults – crumbles, the rest of the nation falters as well. And given cultural expectations around gender roles and caregiving responsibilities within families, it is employed women who tend to carry the heaviest burden.

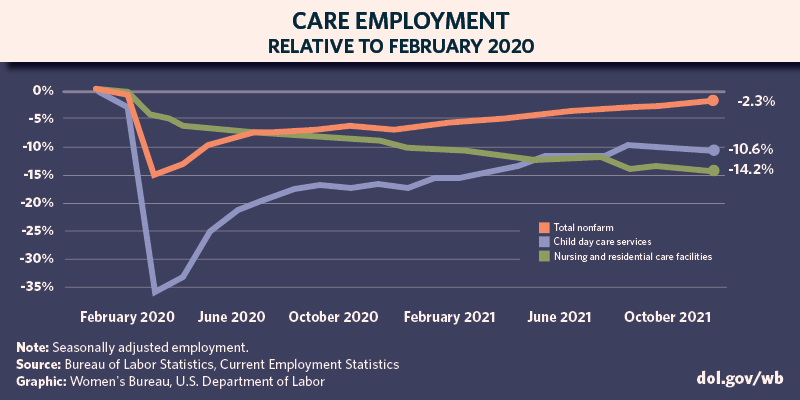

Click to see the source data for total nonfarm, child day care services, and nursing and residential care facilities.

What then, should be done about continued job losses in the care sector? As we have previously covered in this blog series, while the childcare sector has recovered from the significant employment declines experienced in March 2020, 1 in 10 childcare jobs are still “missing” relative to February 2020. Nursing and residential care facilities have fared even worse, with 14.2% lower employment compared to pre-pandemic. These are industries where the overwhelming majority of workers are women, and provide a service that is vital to the continued employment of women (and men) across the entire economy – not to mention their great importance to the health and wellbeing of the nation.

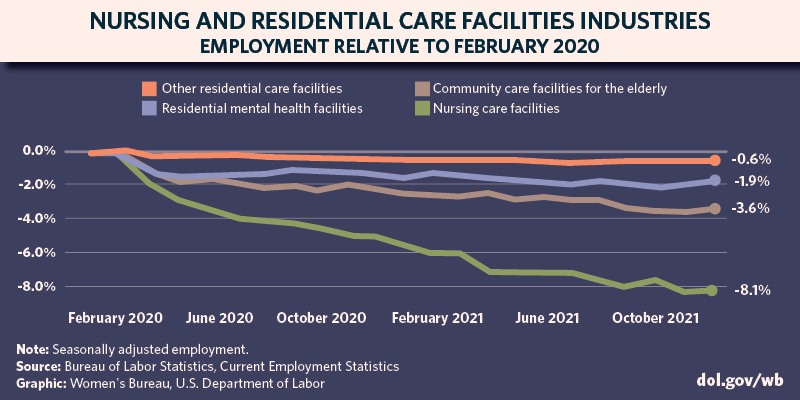

Click to see the source data for nursing care facilities, community care facilities for the elderly, residential mental health facilities and other residential care facilities.

While there are problems across the industry, these jobs losses are especially concentrated in nursing care facilities, which in December 2021 had 240,000 fewer employed workers compared to February 2020. This has tremendous implications for the women who formerly held these jobs, some of whom may have transitioned to other industries but many of whom are likely to be unemployed or pushed out of the labor market. It also should serve as a wakeup call to the rest of the nation, as every one of us has the potential to need access to nursing or residential care facilities for ourselves or our loved ones.

Part of the problem is that these are jobs that have historically offered low wages and few benefits, despite the essential nature of the work. The median hourly wage across nursing and residential care facilities is only $15.16, which is $32,000 a year. Wages are even lower for home health and personal care aides, and nursing assistants, orderlies, and psychiatric aides who make up 4 in 10 workers in the industry; their median hourly wage is only $13.90, or $29,000 a year. This is difficult and important work, but the longstanding lack of investment to support and retain such a vital workforce is having a negative impact on the care infrastructure in the United States.

As the Department of Labor and the Biden administration have repeatedly noted, the economy cannot fully recover if women are left behind. And there cannot be an equitable recovery without addressing the cracks in the nation’s caregiving infrastructure. We must invest in this essential workforce through education, training, increasing wages and enforcement of existing protections and labor standards.

Janelle Jones is the department’s chief economist. Sarah Jane Glynn is a senior advisor in the Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

2021-2017 Blogs and News

Eliminating Violence and Harassment in the World of Work

By: Amy Dalrymple | December 9, 2021

Each year, from Nov. 25 to Dec. 10, the Global 16 Days Campaign brings together governments, international organizations, the public and private sectors, and individuals to raise awareness about and call for the elimination of gender-based violence. This year’s 30th anniversary campaign is focusing on domestic violence and the world of work. The Women’s Bureau joins these efforts to end gender-based violence in the world of work and believes everyone has the right to be safe at work and live in a world free from violence and harassment.

Gender-based violence in the world of work can be the direct result of domestic violence and can affect both women and men, in all their diversity. Gender-based violence not only affects the survivors who experience it, it also affects the entire community around them and can have multigenerational impacts.

Globally, about 1 in 3 women have experienced some form of physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime. In the U.S., 1 in 4 women and 1 in 10 men have experienced domestic violence. Coined the “shadow pandemic,” we’ve seen the rates of domestic violence rise in our communities as COVID-19 social distancing efforts worldwide sent people into isolation and made it harder for survivors to get help. Even before the pandemic, one survey estimated that in the U.S., more than half a million women had missed work in the past year and nearly 8.5 million women had missed work at some point over their lifetime due to intimate partner violence.

Financial independence through employment can help break the cycle of violence and harassment. However, barriers such as domestic violence and workplace harassment prevent women all over the world and in the United States from entering and remaining in the labor force.

One of the Women’s Bureau’s recent initiatives, the Fostering Access, Rights, and Education (FARE) grant program, helps women workers learn about their employment rights and access benefits. These grants are intended to ensure that women who are paid low wages at work, and are otherwise marginalized and underserved, can access the services, benefits and legal assistance they need.

Guam’s Bureau of Women’s Affairs, one of six recent FARE grantees, is addressing workplace harassment among women throughout Guam. University of Guam data indicates that 63% of residents most affected economically by COVID-19 were women. Data also shows that of the 1,030 domestic violence cases reported in 2020, 74% of the survivors were women. Additionally, approximately 78% of workplace establishments in Guam employ fewer than 20 people, and many do not have the resources to address workplace complaints, including workplace harassment.

By conducting targeted, multilingual outreach to communities and small businesses throughout Guam, the Bureau of Women’s Affairs is expecting to connect directly with more than 400 women workers to educate them about workplace harassment, inform them about their rights, and provide access to benefits and resources. They also hope to reach people across Guam via a print, broadcast and social media campaign.

Violence and harassment in the world of work is pervasive across sectors and countries and therefore requires innovative solutions that invest in comprehensive services for survivors, as well as robust prevention efforts. As the world continues to cope with the pandemic, we must take action to eliminate violence and harassment at work.

Learn more about the 16 Days Campaign, and watch an International Labor Organization panel on ending workplace violence and harassment featuring Women’s Bureau Director Wendy Chun-Hoon on Dec. 15.

Amy Dalrymple is a policy analyst in the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

Rebuilding the Economy Requires Rebuilding Care Infrastructure

By: Janelle Jones, Sarah Jane Glynn | December 7, 2021

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ November jobs report shows that the economy is continuing to rebuild. Overall, unemployment continues to tick down, while employment and labor force participation rates are increasing in the aggregate. While full recovery from the unprecedented economic shock of the pandemic will take time, it is encouraging that the economy is rebounding more quickly than the Congressional Budget Office predicted. These beneficial changes in job creation and employment show that the Biden-Harris administration’s policies are moving us in the right direction. However, there is still more work to be done.

View plain text for "Employment Loss by Month" chart

The economy will never be able to fully recover if half of the working age population – women, who experienced the majority of pandemic job losses – are left behind. And in spite of the positive changes seen in this month’s jobs data, many of the concerning trends for women observed last month continue to be true.

Adult women’s employment and labor force participation rates have increased, which is a very good sign. But there are still 2 million fewer employed adult women than there were pre-pandemic, compared to 1.5 million adult men. Adult Black women’s unemployment rate dropped by 2.0 percentage points, which on its face is a big step in the right direction. But this change was caused both by an encouraging increase in Black adult women’s employment and a very discouraging decrease in labor force participation, which means they are no longer looking for work. Black women continue to have the greatest employment losses relative to February 2020.

View plain text for "Employment Losses by Sex, Race, and Ethnicity" chart

Women workers are still down 2.3 million jobs (3.0%), including over 700,000 education and health services jobs since the pandemic began, with women’s employment fully recovered in only four industries: utilities, professional and business services, construction, and transportation and warehousing. Employment in child day care services, where 96% of employees are women, actually decreased slightly between October and November, with the overall industry in much the same place it has been for the last several months. 1 in 10 child day care service workers have either lost their jobs, left the labor force or moved to another field.

While the data on public and private sector education jobs is less clear-cut than that on child care, education jobs are also down from where they were before the pandemic. These jobs encompass not only teaching and administrative positions, but all the support staff like cafeteria workers, bus drivers and afterschool program workers who help keep schools functioning and children cared for. As we are seeing across the economy, the problem is not a lack of workers who are able to do these jobs but rather that the low pay is an insufficient draw for the work required.

The decrease in education and childcare jobs has a doubly negative impact on women, since they both hold the majority of these jobs and are more likely than men to be the family members who scale back on paid work when care for children isn’t available. But the care and supervision of children is not, nor should it be, a women’s issue. Men are parents too, and the availability of child care – whether provided by mothers or other unpaid family members, or by paid professionals – is a necessary component of the American economy. The workers who care for children in day cares, on school grounds, and in afterschool camps and programs, are an indispensable part of working parents’ ability to maintain employment.

This is why the investments in child care, pre-kindergarten, and Head Start contained in the Build Back Better Act are so vitally important to the ongoing economic recovery. Learn more about how Building Back Better is supporting America’s families.

Janelle Jones is the chief economist of the U.S. Department of Labor. Sarah Jane Glynn is senior advisor of the Women’s Bureau. Follow the Women’s Bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

5 Facts About Latinas in the Labor Force

By: Eleanor Delamater, Gretchen Livingston | October 20, 2021

Latinas are now the largest group of women workers in the U.S., behind non-Hispanic whites. Numbering more than 12 million, Latinas account for 16% of the female labor force – a figure that is projected to grow dramatically, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

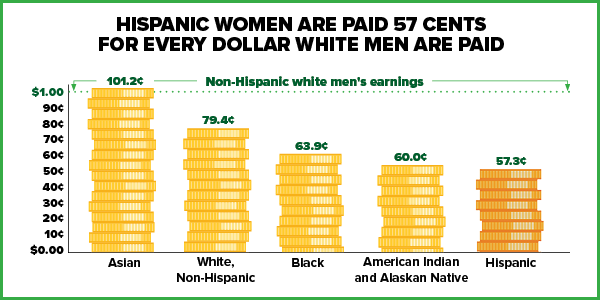

While Latinas play a critical role in America’s workforce, their wages continue to lag significantly behind those of their white male counterparts. This year, Oct. 21 marks Latina Women’s Equal Pay Day, a symbolic representation of the number of additional days Latina women employed full-time, year-round must work, on average, to earn what white, non-Hispanic men earned the year before.

Here are five facts about Latina women in the labor force:

1. Hispanic women experience the largest wage gap of any major racial or ethnic group

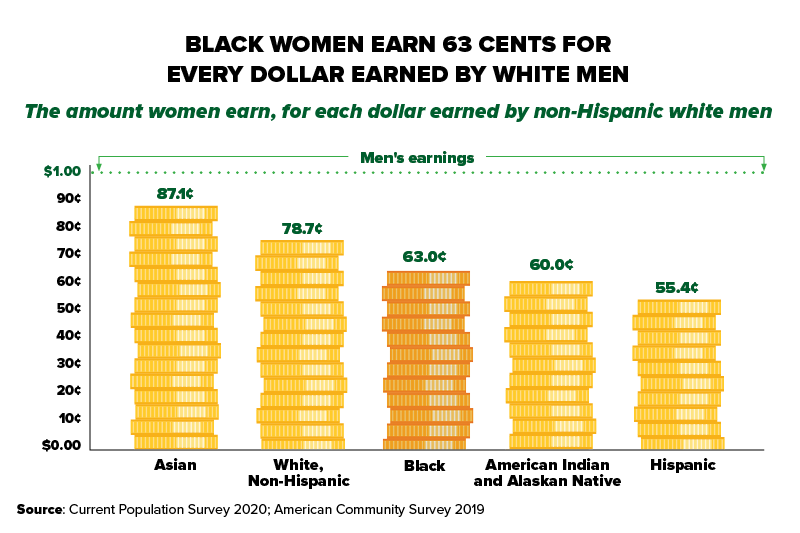

For every dollar earned by a non-Hispanic white man, a Latina earns just 57 cents – a situation no doubt reflected in the fact that almost 1 in 10 (9%) Latinas working 27 hours or more a week are living below the poverty line.

2. Today’s gap reflects a long-standing pattern

Looking back over the past 30 years, Latinas have consistently earned less than 60 cents for every dollar earned by non-Hispanic white men; and today’s gap is only about five cents smaller than it was in 1990. African American women, too, have experienced a five-cent narrowing in the wage gap over that time period. The wage gap has narrowed by more than 10 cents for white women over the past three decades, and for Asian women the gap has closed.

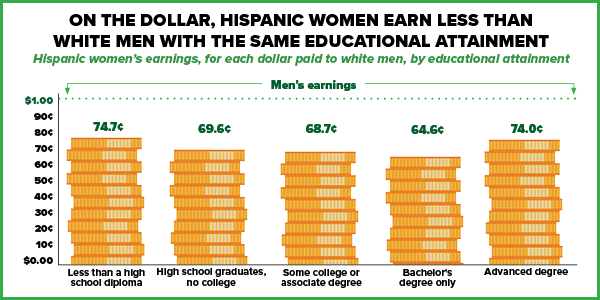

3. The Latina wage gap persists even after controlling for educational differences

Latinas are less likely to have completed education beyond high school than other groups, but this fact does not explain away the entire wage gap. Even within each educational level, their wages remain relatively low compared with white men. For instance, among those with a bachelor’s degree, Hispanic women only make 64.6% of what white, non-Hispanic men make. In fact, Hispanic women with bachelor’s degrees have median weekly earnings less than those of white men with some college or an associate degree.

4. The pandemic hit Hispanic women particularly hard

Hispanic women experienced the steepest initial employment losses of any major group early in the pandemic. In April 2020, almost one-quarter (23%) fewer Hispanic women were working relative to just before the pandemic in February 2020. In comparison, this figure was 19% for Asian women, 18% for Black women and 16% for non-Hispanic white women. While employment has recovered significantly for other groups since that time, it continues to lag for Hispanic women and Black women who are still experiencing relatively large employment losses (5.2% and 4.7%, respectively).

5. Latinas have relatively high labor force participation rates, and unemployment rates

In September 2021, labor force participation for adult Hispanic women was 57.7% and unemployment was 5.6%. In comparison, these figures for adult white women were 56.1% and 3.7%.

Explore more data on women in the workforce and learn more about equity in wages.

Eleanor Delamater is a presidential management fellow and Gretchen Livingston is a survey statistician for the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

5 Things to Know About the Child Tax Credit

By: Analilia Mejia | October 14, 2021

This summer, the Biden-Harris administration’s American Rescue Plan Act increased the 2021 Child Tax Credit (CTC). This historic support – the largest ever credit – is helping families and children struggling to recover financially from the COVID-19 pandemic. The full benefit is now $300 per month, or $3,600 for the year, and any family with children 17 or under who are tax dependents and have a valid Social Security number (regardless of the parents’ immigration status) can access it. Many families automatically received this benefit. Those who haven't received the benefits can easily and quickly apply for them.

Accessing this benefit is fast and simple. Here’s what families interested in applying for the credit need to know:

- There is no minimum income required to get the credit for tax year 2021. Even families who had little to no reported income can be eligible for the full $300 a month. These funds can be used in any way to support the wellbeing of children — child care, education supports, housing and more.

- Mixed status families can access this needed support as long as their children hold valid Social Security numbers and are 17 or under. DACA youth are also eligible. Although parents are not required to have a social security number, they must have an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number to claim the credit for their eligible children.

- The support is significant, with many families eligible for the full annual amount of $3,600. Parents making little to no income, married couples making $150,000 per year or less, or heads of households making up to $112,500 are eligible to receive the full CTC benefit. Families with higher incomes may still be eligible for smaller amounts.

- There is still time for families to receive this support. Eligible families began getting payments in monthly installments in mid-July and will continue receiving those payments through December 2021. When families file their taxes in 2022, they will get the remaining CTC benefit they didn’t get through the monthly installments.

- The payments will come directly to you. If you have a bank account, you can sign up for direct deposit of your CTC monthly payments. If not, provide the mailing address where you’d like the payments sent.

Don’t let your child and family miss out on this historic support. To claim your credit, visit https://www.getctc.org/en. To learn more about the credit, including who is eligible and how to apply, join @WB_DOL for a Twitter chat on Oct. 28, from 1 to 2 p.m. ET, using the hashtag #CTCchat.

Analilia Mejia is the deputy director of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

Advancing Equal Pay at Home and Abroad

By: Thea Lee, Wendy Chun-Hoon | September 17, 2021

Today, we were honored to speak at an International Equal Pay Day 2021 celebration representing the United States, which has recently joined the Equal Pay International Coalition, or EPIC. We are proud to join other EPIC members – including governments, trade unions, businesses and civil society organizations – to work together to eliminate the gender wage gap.

Here at the U.S. Department of Labor, we are putting women at the center of recovery efforts to ensure that we build back stronger and better in the United States and around the world. We are working to increase pay transparency, disrupt occupational segregation, eliminate gender-based employment discrimination, and increase access to paid leave and care for children, older adults, and persons with disabilities to build the economy we all need to thrive.

Around the world, women typically are paid 23% less than men. The pandemic has exacerbated the many challenges women face in the labor market both at home and abroad. Here in the United States, women, especially women of color, have faced some of the steepest job losses due to the pandemic. They also continue to be over-represented in low-paying jobs, especially in the care sector. Many lack access to the paid leave and health care they need to take care of their own families. To help advocate for equity in wages, the department’s Women’s Bureau developed an Equal Pay Day Toolkit with interactive maps and graphics.

The department’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs, or ILAB, works globally to eliminate the gender pay gap by combating violence and harassment, strengthening women’s voices at work, and improving the quality of jobs. For example, ILAB is promoting gender equality and good jobs in the global garment sector through our support of the International Labor Organization’s Better Work program. Better Work factories have reduced gender pay gaps and increased their productivity and profitability by training female supervisors, reducing incidents of sexual harassment and supporting workers’ rights, especially for women.

We are eager to share our insights and good practices gained from our domestic and international efforts to close the wage gap and, in turn, learn from other EPIC members.

Closing the gender wage gap will require concerted efforts from all stakeholders: government, workers’ and employers’ organizations, businesses and civil society. Joining EPIC and its multi-stakeholder coalition is an important step towards achieving the vision of an equal and inclusive world of work.

Wendy Chun-Hoon is the director of the Women’s Bureau. Follow the Women’s Bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

Thea Mei Lee is the Deputy Undersecretary for International Affairs. Follow ILAB on Twitter at @ILAB_DOL.

5 Facts About Black Women in the Labor Force

By: Mathilde Roux | August 3, 2021

Black women are an integral part of the American labor force but have long faced a pay gap due to longstanding inequities in education and the labor market. In addition, they have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. Black women workers are overrepresented in low-paying service sector jobs, which were among the hardest hit, in terms of job losses.

Aug. 3, 2021, marks Black Women’s Equal Pay Day, a symbolic representation of the number of additional days Black women working full-time, year-round, must work, on average, to earn what white, non-Hispanic men earned the year before.

Here are five facts about Black women in the labor force:

1. Black women earn 63 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men

Black women’s earnings are 63.0% of white, non-Hispanic men’s earnings – the third-widest gap after Native women (60%) and Hispanic women (55.4%). In comparison, white, non-Hispanic women earn 78.7% of white, non-Hispanic men’s earnings, and Asian women earn 87.1%.

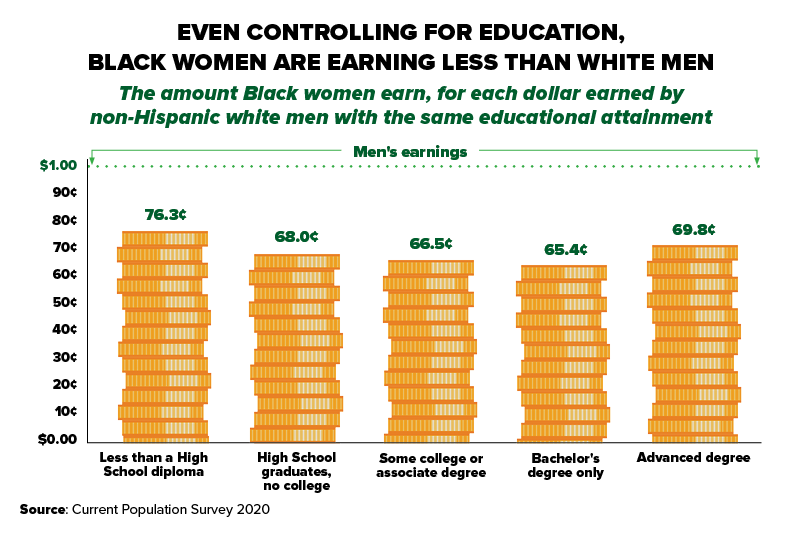

2. This wage gap is not just driven by educational differences

Even controlling for education, Black women still earn less than their white male counterparts. Among those with a bachelor’s degree, Black women only earn 65% of what comparable white men do, for instance. And among people with advanced degrees, Black women earn 70% of what white men do. In fact, Black women with advanced degrees have median weekly earnings less than white men with only a bachelor’s degree.

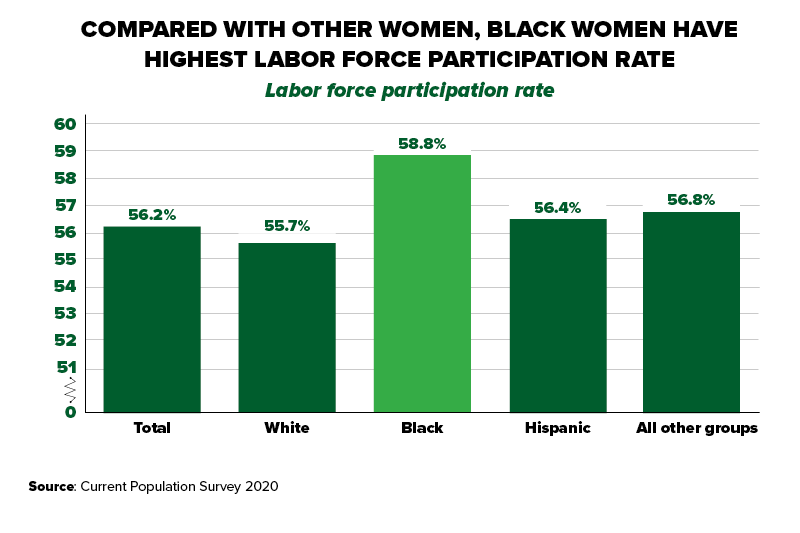

3. Black women have the highest labor force participation rate of all women

Typically, Black women have higher labor force participation rates than other women, meaning a higher share of Black women are either employed or unemployed and looking for work. For instance, in 2019, Black women's labor force participation rate was 60.5% compared with 56.8% for white women. Even in 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, their labor force participation rate was 58.8%, compared to 56.2% for women overall.

4. Black women have also experienced high unemployment, especially in the wake of the pandemic

In 2020, Black women’s unemployment rate was 10.9%, compared to 7.6% for white women and 8.3% for all women. This is no doubt reflective of the steep job losses and slow job recovery experienced by this group since early 2020, though even prior to the pandemic, their unemployment was relatively high (5.6%) compared with white (3.2%), Asian (2.7%) and Hispanic (4.7%) women.

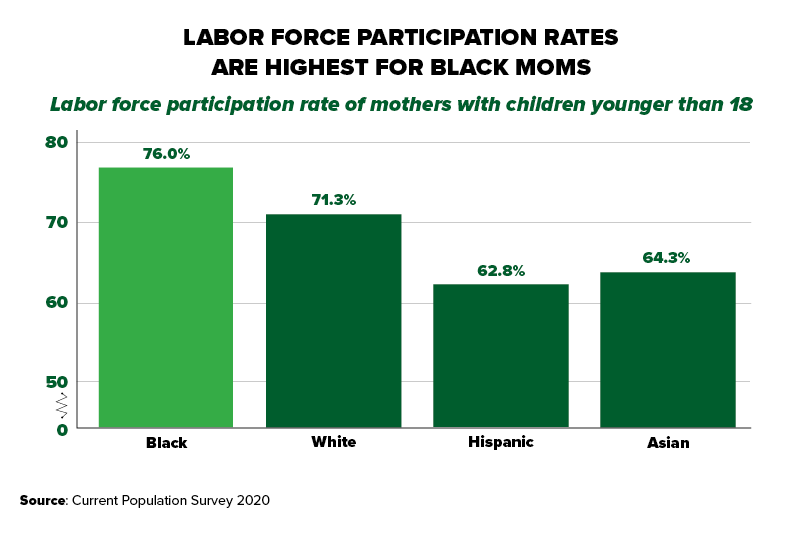

5. Black moms, too, have relatively high labor force participation rates

Black mothers – two-thirds of whom are equal, primary or sole earners in their households – have higher labor force participation rates than other moms. This has historically been the case, and 2020 was no exception: 76.0% were in the labor force, compared with 71.3% of white moms, 62.8% of Hispanic moms and 64.3% of Asian moms.

Mathilde Roux is a Presidential Management Fellow in the department's Women's Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter @WB_DOL.

More Than Statistics: How COVID-19 is Impacting Working Women

By Eleanor Delamater, Gretchen Livingston | July 21, 2021

Over the past several months, the Women’s Bureau has been asking women to tell us about their personal experiences during the pandemic, and what support they need going forward. We’ve heard from women all over the country who work in all different occupations and industries. Many have shared similar observations about what would help them in the workforce: paid leave, access to child care, flexible work arrangements and supports for transitioning back to the workforce. Here are just a few of their stories. For Jesse and LaTanya, having a national, comprehensive paid medical and family leave policy would have helped them maintain financial stability throughout the pandemic and beyond. Jesse, a single mom, lost her job and ultimately her home when she contracted COVID. Meanwhile, LaTanya had to choose between her financial security and the health of her baby with respiratory issues. | ||

| When the pandemic hit I was a self-sustaining single mom of my 15-year-old daughter working at [a big box store] as head cashier. I got really sick with Covid and I was terminated during my paid leave for it. For 2 months I fought for my position to be reinstated and it finally was. But we lost our home and I got much sicker during those 2 months. We are living with my 87-year-old grandmother and I'm advocating for there to be a stricter leave law in place for anyone who catches Covid especially while working as an essential employee! – Jesse, Tennessee |  | |

So when Covid hit I was working in the medical field and had a very young baby, who experiences breathing difficulties. So having that in the back of my mind I felt the right thing to do in the situation was to protect her the best way I knew how, which was to leave [my] job and just stay with her full-time. At one point I was facing eviction and even about to have my car repossessed. But, my daughter's health and safety was/is way more important to me than any material things. Covid has not been all bad for me though. I was able to watch my daughter take her first steps. I'm so glad I got to see that! – LaTanya, Missouri |

|

|

Blair has struggled with new motherhood during COVID, especially given the lack of child care options. Work flexibility has helped her manage, but she’s not sure how much longer that will be an option for her. |

| |

Being a first-time mom during a global pandemic has been an experience, that's for sure! I was pregnant, gave birth, had 3 months of maternity leave, and returned to work all during the COVID-19 pandemic. My original plan of daycare had to change. I've had to ask for an exception to continue to work from home ... Trying to manage breastfeeding, working 40 hours a week, and managing the care for a baby has been one of the biggest challenges of my life. – Blair, Illinois |  |

|

Like many, Mary lost her small business. She wants to get back to work, but needs support finding employment, and job flexibility so she can fulfill her caregiving responsibilities, too. |

| |

I was a business owner in Las Vegas and due to pandemic lost my business. I would still like to work but have been out of the job market for some time. I have been receiving [Pandemic Unemployment Assistance] but I am now being asked to apply for jobs. I received no help with small business loans or any help from state, federal or local entities. I cannot go back into the work place because of my husband’s disability and the lack of job skills. What kind of help is available to me? – Mary, Nevada

|

| |

Then there are women like Shara, who remind us just how resilient we can be, and that we have to not only recover, but build a new, better economy that works for everyone. |

| |

Covid came blasting into our lives taking away but it also enriched us to find more innovative ways to reach out – more phone calls and video chats – realizing we had to realign our priorities to embrace those that we love... I rise to see if I can make a difference and I will continue to contribute – I am proud to be a [woman] and all that we stand for. – Shara, Colorado |  |

|

This pandemic has disproportionately impacted women. The adult women’s employment rate (54.3%) is at its lowest pre-pandemic level since September 1988 (54.1%). In June, there were 7.2% fewer adult Black women, 5.9% fewer adult Hispanic women, and 4.8% fewer adult white women employed compared with February 2020.

Mothers of young children had the steepest reductions in employment during 2020. Among mothers with children under the age of 13, 1.2 million fewer mothers were working, representing loss of about 7% of employed mothers ages 25-54.

But working women are more than just statistics. They are human beings with names, unique stories and individual challenges that require solutions. To meet the demands of a recovering economy, without giving short shrift to family and individual care needs, these women, and so many more who toil in anonymity, need a comprehensive national paid leave program, access to affordable child care, and workplaces willing to accommodate the needs of working families. This moment is ripe with opportunity to re-envision the full spectrum of work-family policies necessary to create a workforce that is better and stronger than it was pre-pandemic.

Eleanor Delamater is a presidential management fellow and Gretchen Livingston is a survey statistician for the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

We want to continue to hear about your unique challenges and what solutions you need in order to best advocate for all working women. Please share your story with us: https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/wb100/story

Even Prior to Pandemic, Working Women Couldn’t Take Time Off When They Needed

by Gretchen Livingston | June 17, 2021

The COVID pandemic has thrown into sharp relief the struggles of working women in the U.S., amplifying the challenges they face as they try to succeed in the labor market while juggling family and personal responsibilities.

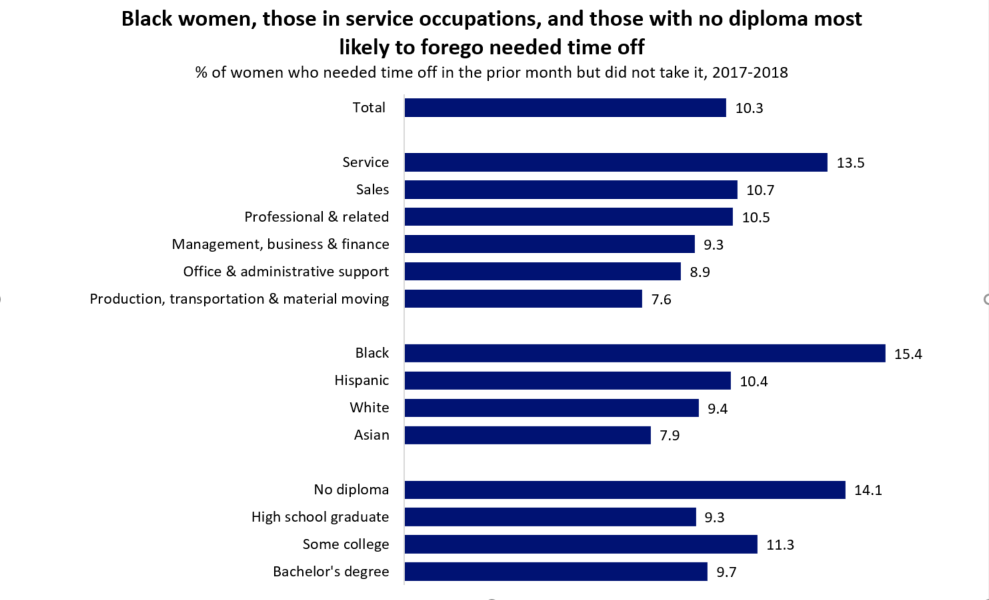

Even before COVID, though, many were in the position of needing time off but not being able to take it. Indeed, among all working women in the U.S., 1 in 10 had that exact experience in the prior month, according to the 2017-2018 American Time Use Survey Leave Module, a nationally-representative survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics sponsored by the Women’s Bureau.

Notes: Based on the main job of employed civilian, non-institutionalized women ages 16 and older. Results not shown for women in Natural resources, construction & maintenance due to insufficient sample size. Hispanics may be of any race. Data: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey Leave Module 2017-2018. Graphic: U.S. Department of Labor Women's Bureau. (plain text chart below)

Women working in service occupations – who were also the least likely to have access to paid leave – were among the most likely to report having needed but not taken leave (13.5%). The shares foregoing leave were also high among African American women (15.4%) and those lacking a high school diploma (14.1%).

On the flip side, women working in production, transportation and material moving, and Asian women were among the least likely to report having needed but not taken leave (7.6% and 7.9% did so, respectively).

Notes: Based on the main job of employed civilian, non-institutionalized women ages 16 and older. Respondents could provide more than one reason. Data: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey Leave Module 2017-2018. Graphic: U.S. Department of Labor Women's Bureau. (plain text chart below)

By far the largest share of all women who needed but didn’t take leave (42%) reported needing to take off for their own illness or medical care. Sizeable shares also reported needing time off for errands or personal needs (26%), or to care for a family member who was ill or had medical needs (20%). Some 8% needed but did not take time off for child care (respondents could report more than one reason for needing time off).

Why in these cases did women not take leave? For many, taking off was simply not an option: 12% said that they could not afford to lose the income, 11% were denied leave, and 10% feared reprisals for taking time off, for instance.

Notes: Based on the main job of employed civilian, non-institutionalized women ages 16 and older. Respondents could provide more than one reason. Data: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey Leave Module 2017-2018. Graphic: U.S. Department of Labor Women's Bureau.(plain text chart below)

Women were equally likely to report foregoing needed time off, whether they had access to paid leave or not. However, the experiences of these two groups of women did differ in other ways. Those who didn’t have paid leave were more likely to say they needed the time off to care for their own illness or medical needs (50% vs. 35%), and were almost five times more likely to say that they didn’t take off because they could not afford to do so (24% vs. 5%).

In contrast, women with paid leave were slightly more likely to say that they needed the leave for errands or other personal reasons (29% vs. 22%) and were more likely to forego the leave because they had too much work (29% vs. 12%).

Notes: Based on the main job of employed civilian, non-institutionalized women ages 16 and older. Data: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey Leave Module 2017-2018. Graphic: U.S. Department of Labor Women's Bureau. (plain text chart below)

The snapshot of data here reveals that pre-pandemic, 1 in 10 women reported unmet need for leave in the month prior, and these needs seemed particularly acute for those lacking paid leave. The struggles brought on by COVID since that time have been so wide ranging, so overwhelming and so salient, that the national conversation about paid leave, personal care and care work responsibilities has been elevated in a new way.

A number of states and cities in the U.S. have already adopted some form of paid leave legislation, as have all other OECD nations. It is past time for policymakers to do the same at the national level, so that we can begin to benefit from a new normal where all workers are able to care for themselves and their loved ones without losing their paychecks in the process.

Gretchen Livingston is a survey statistician in the department’s Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

Chart data

| Black women, those in service occupations, and those with no diploma most likely to forego needed time off | |

| % of women who needed time off in the prior month but did not take it, 2017-2018 | |

| Total | 10.3 |

| Service occupations | 13.5 |

| Sales | 10.7 |

| Professional & related | 10.5 |

| Management, business & finance | 9.3 |

| Office & administrative support | 8.9 |

| Production, transportation & material moving | 7.6 |

| Black | 15.4 |

| Hispanic | 10.4 |

| White | 9.4 |

| Asian | 7.9 |

| No diploma | 14.1 |

| High school graduate | 9.3 |

| Some college | 11.3 |

| Bachelor's degree | 9.7 |

| Notes: Based on the main job of employed civilian, non-institutionalized women ages 16 and older. Results not shown for women in Natural resources, construction & maintenance due to insufficient sample size. Hispanics may be of any race. Data: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey Leave Module 2017-2018 | |

Biggest share of working women who forego time off need it for their own health care. % of women who needed but didn't take time off in the prior month, by reason for needing it, 2017-2018 | |

| For own illness or medical care | 41.6 |

| Errands or personal reasons | 25.7 |

| To care for sick family member | 19.8 |

| Child care | 7.7 |

| Vacation | 4.0 |

| Eldercare | 2.4 |

| Other | 1.1 |

| Birth or adoption | 0.0 |

Notes: Based on the main job of employed civilian, non-institutionalized women ages 16 and older. Respondents could provide more than one reason. Data: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey Leave Module 2017-2018 | |

For many women, taking time off is not an option. % of women who needed but didn't take time off in the prior month, by reason for not taking it, 2017-2018 | |

| Could not afford the lost income | 12.5 |

| No one to cover shift | 8.3 |

| Leave request denied | 11.4 |

| Made alternate plan | 5.3 |

| Fear of job loss/reprisal | 9.7 |

| Didn't have enough leave | 8.0 |

| Didn't have any leave | 8.5 |

| Wanted to save leave | 5.2 |

| Too much work | 22.4 |

| Other | 9.7 |

Notes: Based on the main job of employed civilian, non-institutionalized women ages 16 and older. Respondents could provide more than one reason. Data: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey Leave Module 2017-2018 | |

Women with no paid leave more likely to forego time off for their own health needs and due to financial concerns. % among women in 2017-2018 who needed but didn't take time off in the prior month who… | ||

| Have paid leave | Don't have paid leave | |

| Needed leave for own illness or medical care | 35.2 | 48.6 |

| Didn't take leave because they couldn't afford to lose the income | 5.1 | 24.3 |

Notes: Based on the main job of employed civilian, non-institutionalized women ages 16 and older. Data: Bureau of Labor Statistics, American Time Use Survey Leave Module 2017-2018 | ||

Let’s Make Equal Pay a Reality

by Charmaine Davis | June 10, 2021

The Equal Pay Act was passed on June 10, 1963, but 58 years later women continue to earn less than men.

Two recently released analyses from the Women’s Bureau show that, on average, women earn 80% to 83% of what men do, and most of this gender wage gap cannot be explained by differences in men’s and women’s work histories, work hours, industry and occupation distribution, or job characteristics.

On average, women working full-time, year-round earned $47,299 in 2019 while men working full-time, year-round earned $57,456. For women of color the wage gap is even greater: Black women earn 63% of what white non-Hispanic men are paid and Latinas are paid 55% as much.

Occupational segregation, the devaluation of work traditionally done by women, and caregiving penalties that fall disproportionately on women all contribute to the wage gap. Our recent research confirms that occupations employing a larger share of women paid lower wages on average than similar male-dominant occupations, and these wage differences could not be explained away by the characteristics of the workers or the requirements of the jobs.

At the same time that women are sorted into lower-wage work, many also experience wage penalties related to their caregiving responsibilities. Only 20% of U.S. workers have access to paid family leave through work, and in part-time jobs and the service sector – where many working women are concentrated – it is often difficult to take leave without work-related repercussions. This means workers who care for children or elderly parents may have to choose between taking care of their loved ones when they are ill or losing a day’s worth of pay, if not their job.

As the country emerges from the pandemic, we don’t want to simply return to “normal” – we want to build back better and provide an equitable recovery for all workers. Let’s realize the aspirations of the Equal Pay Act by supporting the logical next steps that will move us toward true pay equity.

It’s on us to end to the insidious vestiges of gender-based pay discrimination, create pathways to good-paying jobs for women, value the jobs traditionally held by women, and provide a work-life balance that encourages women’s participation in our economy by expanding access to paid leave.

At the Women’s Bureau, we are expanding pathways to higher-paying jobs via the Women in Apprenticeship and Nontraditional Occupations (WANTO) grant program, which seeks to increase the number of women in registered apprenticeships and historically male-dominated jobs. We’re also developing a database to track child care costs and how they relate to women’s labor force behavior, and are working to document the long-term financial costs of caring, which fall disproportionately on women.

Policies to promote equal pay are essential to helping everyone succeed, both men and women alike. As Women’s Bureau Director Wendy Chun-Hoon says, “If the economy doesn’t work for women, it doesn’t work.”

Charmaine Davis is the regional administrator for the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau in the Southeast, Midwest and South Central states. Follow the bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

Building on a Century of Progress

By Wendy Chun-Hoon | June 4, 2021

What do an English text book, a name badge and desk plate and a baby pacifier have in common? These were four of the items the Women’s Bureau presented to President Bill Clinton in a sealed time capsule for the agency’s 75th anniversary in 1995. These items, along with a movie script, a computer disk, sewing supplies, an EEG printout and more, represented the trades of 22 working women. While much has changed since then, there are striking similarities in the workplace challenges described in 1995 and those voiced by women in 2021 – challenges exacerbated over the last year by the devastation of COVID-19.

Unfortunately, the capsule broke before our centennial anniversary last year – in some ways an apt metaphor of the challenges working women have long endured.

For more than a century, the Women’s Bureau has supported women workers on their professional journeys, advocating for workplace and policy change that address gender-based employment inequities out of the realm of the purely personal and embeds them firmly in public discussion of policy solutions. We have been and continue to be diligent reporters, prescient visionaries and ardent advocates, documenting the experiences of women on the job, anticipating future trends and drawing new roadmaps to cultivate better workplaces.

COVID-19 has amplified the importance of the Women’s Bureau’s mission. It has brought the essential nature of the paid and unpaid work that women do into stark relief – from the frontlines of public health, education, caregiving and food service, to our own homes. It has revealed the glaring disconnect between the fundamental necessity of certain work and the correspondingly low wages and benefits for those who perform the work, predominantly women of color.

The global pandemic has made more urgent our call for paid leave, accessible and affordable child care, equal pay and health insurance. It has elaborated what we have always known: that women’s work is valuable work, and that workplace flexibility and family-friendly practices enhance businesses operations and economic productivity. With the right work-family supports, combined with workplaces free from discrimination and harassment, and level playing fields where equal opportunity wins the day, women and families thrive, and industry prospers.

Over the years, the Women’s Bureau has articulated novel frameworks to improve the workplace for women. From its first decades, when the agency’s mission was shaped by the industrial revolution and two world wars, the Women’s Bureau continually adapted to the increasing volume and diversity of women workers.

In the 1960s, the final report of the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, outlined a unified agenda to address the barriers faced by women in the workplace, including the need for paid leave, affordable child care and elimination of racism against black women.

In the 1970s, we published curricula to move women into the trades. By the 1980s we held the first conference on “contingent workers,” and established the work and family clearinghouse. In the 1990s our research report, “Unnecessary Losses” documented the need for the Family and Medical Leave Act and paid leave.

At the dawn of the 21st century, we pushed for equity in STEM jobs and the emerging tech sector and we called attention to the unique challenges of women with disabilities; immigrant and Native women; women veterans; military spouses; black, brown and Asian women; teen parents and older women workers.

As we look toward the next hundred years of service, we recognize that we have a unique opportunity to build on the work of our predecessors and create new and better solutions for working women. The pandemic eroded women’s employment gains in material ways, the extent and persistence of which is not yet fully understood. The American workplace is constantly changing, bringing new (and in some cases exacerbating all-too-familiar) challenges. The difficulties are real, but we have the tools and the blueprint to construct a more just and equitable workplace. We must meet this moment with a once in a generation opportunity to transform conditions for work and workers that build our economy. That means implementing policies that deliver the opportunity, flexibility and equity to level the playing field for the diverse community of America’s women workers.

Wendy Chun-Hoon is the director of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. Follow the Women’s Bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

The Diverse Experiences of AANHPI Women at Work

By: Hari Chon, Gretchen Livingston | May 21, 2021

While Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander women are often referred to collectively, they are far from a monolithic group. Instead, the AANHPI population includes many groups with varying demographic profiles, histories and experiences in the U.S. Some have resided here for a century, while others have a much more recent immigrant experience. Some came to this country to attain a higher education, while others arrived as refugees with perhaps nothing but the clothes on their backs. Many live and work in California and Hawaii, while others are scattered across the nation.

At the Women’s Bureau, we believe one way to help AANHPI communities is through data-driven storytelling. As we celebrate the cultural diversity of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders this May, here are some key statistics about the 8.5 million AANHPI women in the U.S., more than 5 million of whom are in the labor force.

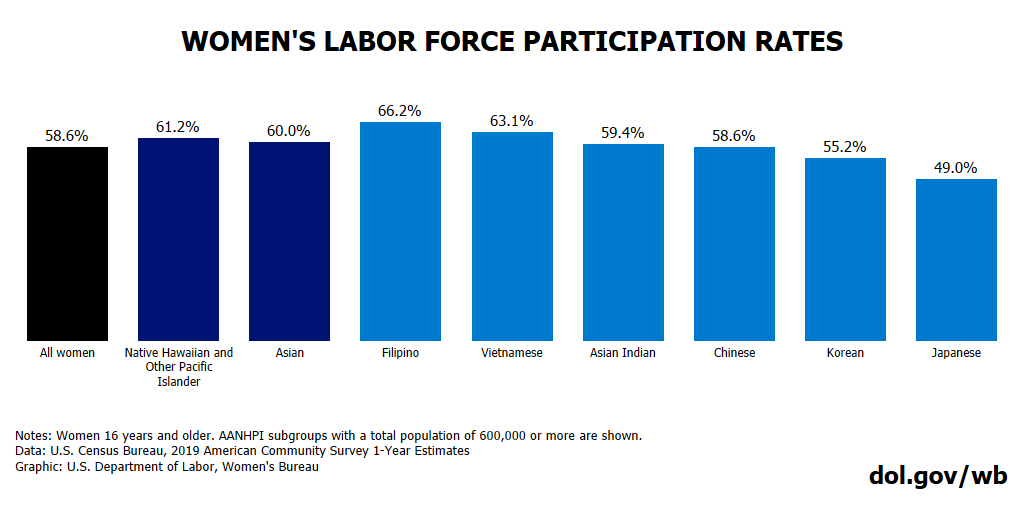

1. Labor force participation rates vary significantly within AANHPI groups.

Two-thirds of Filipinas were in the labor force in 2019, compared with about half of Japanese American women, and 59% of all women.

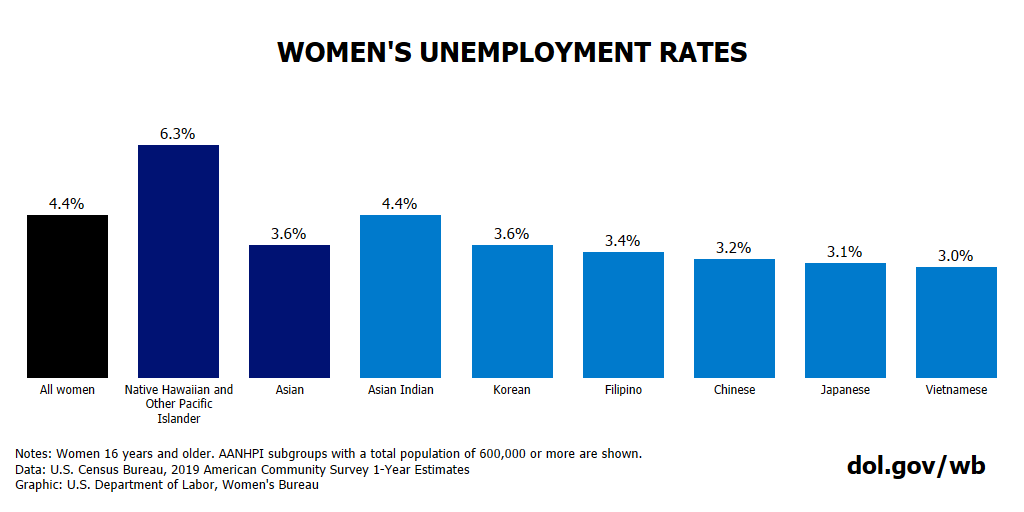

2. Unemployment rates also varied significantly.

Among AANHPI women in the labor force, the share that were unemployed was the highest among Pacific Islanders (6.3%). Unemployment rates were about half as high for Vietnamese, Japanese and Chinese women. In comparison, 4.4% of all U.S. women in the labor force were unemployed in 2019.

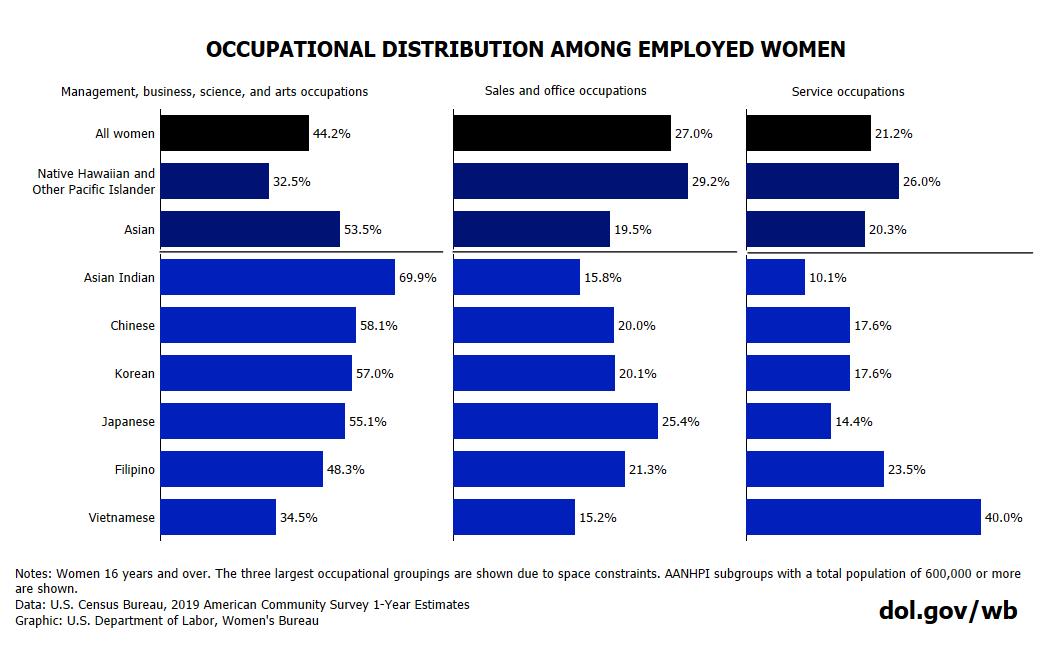

3. The occupational profiles of AANHPI women in the U.S. varied dramatically.

While 70% of employed Asian Indian women work in management, business, science and the arts, the share of Pacific Islander women and Vietnamese American women who do so is only half as high. Meanwhile, relatively large shares of these two groups are employed in service and sales.

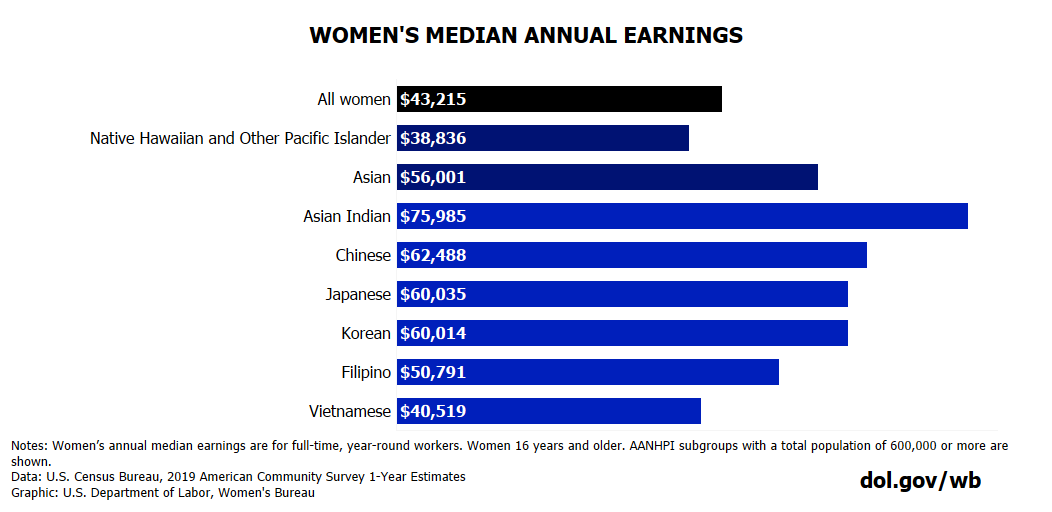

4. Differences in occupational composition across subgroups likely explain dramatic earnings differences.

Indian American women, who were concentrated in managerial and professional occupations, have median annual earnings of about $76,000. Pacific Islander and Vietnamese American women, who were concentrated in sales and service occupations, have the lowest median wages ($38,900 and $40,500, respectively). To put this in perspective, the median wage is $43,200 for all women employed full time.

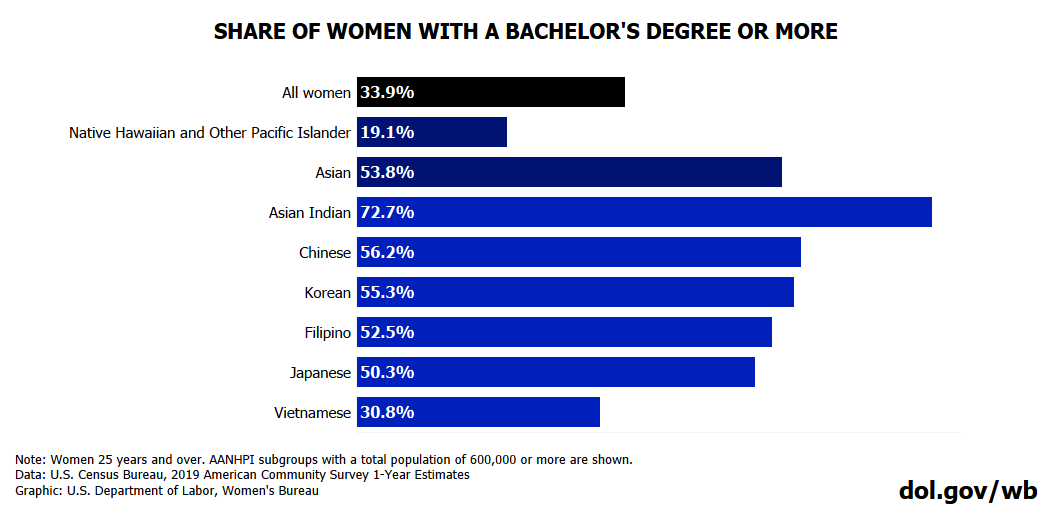

5. Underlying many of these labor force differences are stark educational differences.

While almost three-fourths of Asian Indian women have earned at least a bachelor’s degree, the same is true for only 31% of Vietnamese and 19% of Pacific Islander women. On the flip side, the share of women who lack a high school diploma ranges from 27% among Vietnamese American women to 5% among Japanese American women.

Even looking only at the largest AANHPI groups in the U.S., we see tremendous diversity. Recognizing this diversity can help us develop more effective policies and programmatic interventions across these communities. Thinking of AANHPI women as one group masks their vastly different experiences in the U.S. labor force. Breaking down the data is one way we’re helping AANHPI working women and making their voices heard.

Hari Chon is a policy analyst and Gretchen Livingston is a survey statistician at the U.S. Department of Labor's Women's Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

Technical note on Asian Americans and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders:

These analyses are based on the following single-race classifications:

Asian: a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand and Vietnam. It includes people who indicate their race as "Asian Indian," "Chinese," "Filipino," "Korean," "Japanese," "Vietnamese" and "Other Asian" or provide other detailed Asian responses.

Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa or other Pacific Islands. It includes people who indicate their race as "Native Hawaiian," "Guamanian or Chamorro," "Samoan" and "Other Pacific Islander" or provide other detailed Pacific Islander responses.

| Women's labor force participation rates | |

| Race and ethnicity | LFP rate |

| All women | 58.6 |

| Asian | 60.0 |

| Asian Indian | 59.4 |

| Chinese | 58.6 |

| Filipino | 66.2 |

| Japanese | 49.0 |

| Korean | 55.2 |

| Vietnamese | 63.1 |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 61.2 |

Notes: Women 16 years and older. AANHPI subgroups with a total population of 600,000 or more are shown. Data: U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates

| Women's unemployment rates | |

| Race and ethnicity | rate |

| All women | 4.4 |

| Asian | 3.6 |

| Asian Indian | 4.4 |

| Chinese | 3.2 |

| Filipino | 3.4 |

| Japanese | 3.1 |

| Korean | 3.6 |

| Vietnamese | 3.0 |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 6.3 |

Notes: Women 16 years and over. AANHPI subgroups with a total population of 600,000 or more are shown. Data: U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates

| Occupational distribution among employed women | |||

| Race and ethnicity | Management, business, science, and arts occupations | Service occupations | Sales and office occupations |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 32.5 | 26.0 | 29.2 |

| Vietnamese | 34.5 | 40.0 | 15.2 |

| All women | 44.2 | 21.2 | 27.0 |

| Filipino | 48.3 | 23.5 | 21.3 |

| Asian | 53.5 | 20.3 | 19.5 |

| Korean | 57.0 | 17.6 | 20.1 |

| Japanese | 55.1 | 14.4 | 25.4 |

| Chinese | 58.1 | 17.6 | 20.0 |

| Asian Indian | 69.9 | 10.1 | 15.8 |

Notes: Women 16 years and over. The three largest occupational groupings are shown. AANHPI subgroups with a total population of 600,000 or more are shown. Data: U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates

| Women's median annual earnings | |

| Race | Median earnings |

| All women | $43,215 |

| Asian | $56,001 |

| Asian Indian | $75,985 |

| Chinese | $62,488 |

| Filipino | $50,791 |

| Japanese | $60,035 |

| Korean | $60,014 |

| Vietnamese | $40,519 |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | $38,836 |

Notes: Women’s annual median earnings are for full-time, year-round workers. Women 16 years and older. AANHPI subgroups with a total population of 600,000 or more are shown. Data: U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates

| Share of women with a bachelor's degree or more | |

| Race | Bachelor's degree or higher |

| All women | 33.9 |

| Asian | 53.8 |

| Asian Indian | 72.7 |

| Chinese | 56.2 |

| Filipino | 52.5 |

| Japanese | 50.3 |

| Korean | 55.3 |

| Vietnamese | 30.8 |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 19.1 |

Note: Women 25 years and over. AANHPI subgroups with a total population of 600,000 or more are shown. Data: U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates

A Year of Challenges and Progress, With More Work Ahead

By Hari Chon | May 17, 2021

This year, National Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Heritage Month feels different. On the one hand, longstanding prejudice and discrimination towards Americans of Asian Pacific descent has been heightened as a result of the pandemic.

At the same time, we’re celebrating unprecedented representation – including the first female, Black and Asian Vice President, Kamala Harris, the first Asian American U.S. Trade Representative, Katherine Chi Tai, and new members of Congress of East Asian, Southeast Asian, South Asian or Pacific Islander descent. Asian Pacific Americans are the second fastest-growing population among major race and ethnic groups, and their stories are central threads in the fabric of our shared history.

Amid the global pandemic and the rise in acts of violence against AANHPI Americans, the public-facing nature of industries where Asian Americans figure prominently – as healthcare workers, small business owners and food service workers – pose very real risks to the health and well-being of Asian American workers and proprietors. Beyond the health impacts, the economic impacts of the pandemic on Asian Americans have been substantial. According to the Census Bureau, a quarter of the nation’s 578,000 businesses owned by this group belonged to the Accommodation and Food Services sector, which was particularly hard hit by the pandemic.

The negative impact of the pandemic on the restaurant industry was deeply personal to me. Like many Asian immigrants, my parents built a loyal customer base with our family restaurant, a labor of love and commitment with a proud 18-year history in our community. Despite setbacks and challenges along the way, my parents will tell you that the American Dream is alive and well for Asian Pacific American communities and that theirs is still being written.

The growing numbers and greater visibility of AANHPI leaders, including women in positions of power, gives me hope for the future. Their stories of perseverance encourage all of us to keep moving forward even in the face of challenge and adversity. While the past year has witnessed an increase in acts of aggression and hatred towards members of the Asian Pacific American community across the nation, I am still heartened by what I see as clear evidence of renewed commitment to a set of shared values that demands fairness, equity and justice.

Let us take this moment to celebrate how far we’ve come, and also to recommit ourselves to the obligations of our shared humanity such that our fellow Asian Pacific American friends, family and neighbors never again have to endure a year like the past one.

Hari Chon is a policy analyst in the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

5 Facts on Moms, Work and COVID-19

by Wendy Chun-Hoon | May 6, 2021

With widespread closures of schools and childcare centers, COVID-19 kicked away the scaffolding of care working families rely on to balance the demands of work and family. Mothers, in particular, have borne a heavy load.

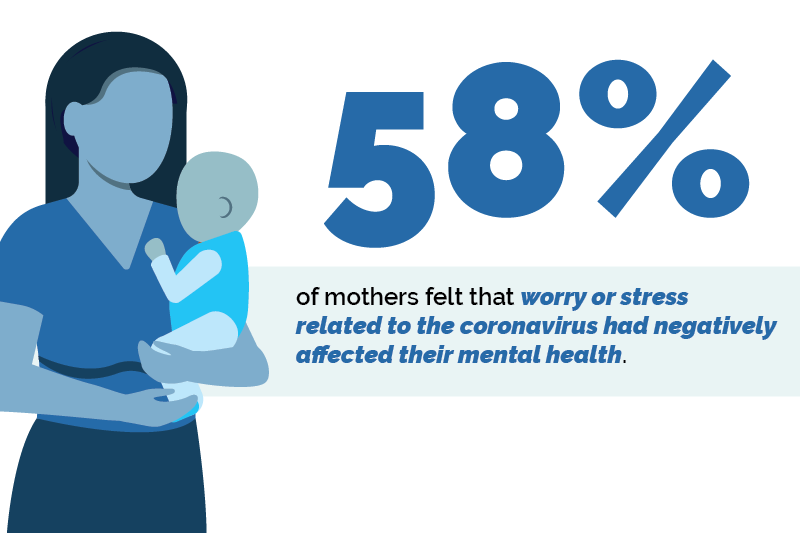

While the amount of time and energy they spend on unpaid labor at home has skyrocketed, their employment has suffered. Along with increases in household food insecurity, many moms also reported other effects of the pandemic beyond the labor market, including increased stress and anxiety. As the United States approaches its second pandemic Mother’s Day, here are five facts about how the pandemic has affected moms.

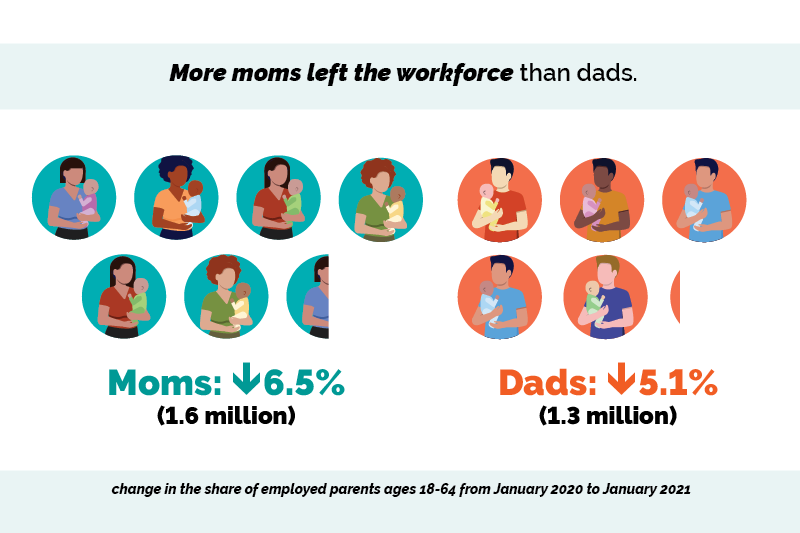

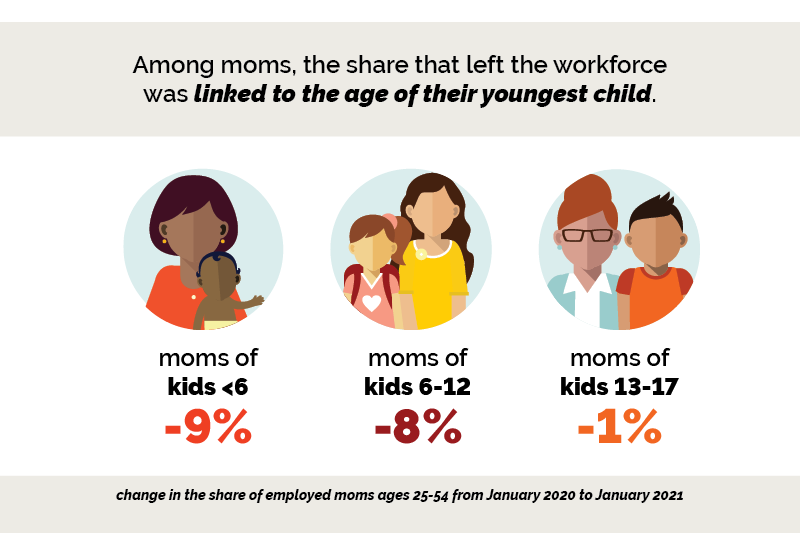

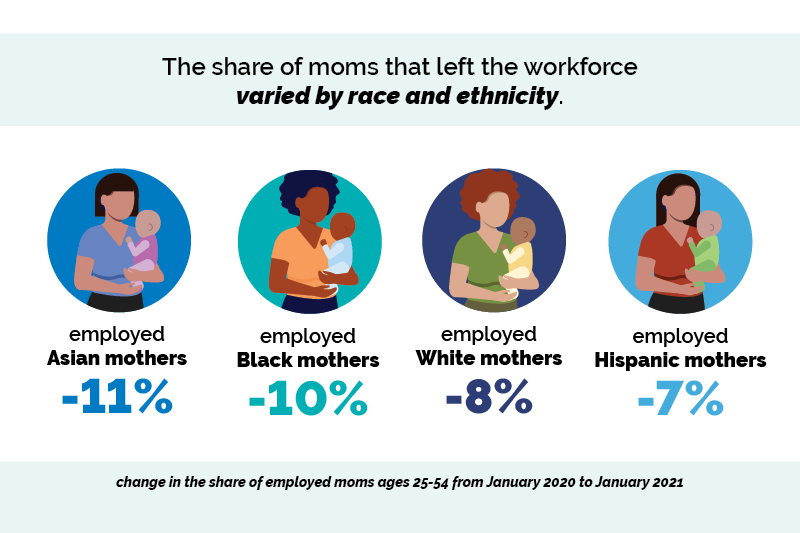

1. Maternal employment took a hit due to school and daycare closures